In response to the 2014 Slow Meat conference held in Denver, CO on June 20-22, Slow Food Western Slope hosted our own Slow Meat event on July 12 at the Paradise Theatre.

Megan MacMillan used wonderful, local meat products to highlight what the North Fork Valley has to offer. Her offerings included pulled pork shoulder, Black Welsh Mountain sheep ribs and heritage American Bronze Turkey.

To view the menu and some goodies that Megan prepared, visit the Slow Meat North Fork photo gallery.

We had special guest speakers: Susan Raymond, Alison Gannett of Holy Terror Farm, Wink Davis of Mesa Winds Farm & Winery plus Jake Gray, a young farmer working at The Living Farm who has started to raise chickens.

The attendees enjoyed the movie, American Meat.

So what is Slow Meat anyway?

The purpose of Slow Meat is to consider our food system’s successes and failures to deliver good, clean and fair meat in an age of industrialized food, capital concentration, and diminished choices. More than any other food, meat is emblematic of the challenges and opportunities for the production, processing, distribution, marketing and consumption of meat in America and beyond.

Slow Meat was a three-day symposium that brought together over 100 stakeholders from across the USA to share expertise in facilitated discussions and planning. Slow Food USA’s goal was to produce a menu of practical actions for Slow Food communities across the USA to deploy, measure, refine and report back to a larger national community of advocates who seek change in our food system.

Slow Meat’s goal is “better meat, less”. (One can interpret this slogan as: more animals on the ground, less in captivity; less animals hogging up the center of the plate (i.e., 1950s meat and potato) and more as flavor.)

Here’s more discussion regarding Slow Meat:

While many Coloradans are foregoing meat because of health or environmental concerns, not all meat is created equal. Investing in sustainably raised slow meat can help mitigate climate change, protect Colorado’s grasslands, and generate income for ranchers. It is both nutritious and delicious.

Slow Food USA is holding its first-ever Slow Meat symposium in Denver this month to discuss the challenges and innovations in raising animals for food. There, delegates from across the country will gather to draw upon each other’s experience and ideas to create a menu of action items that will promote local solutions to meat’s biggest challenges.

Cattle are often seen as the methane producing culprits of climate change, but grass-fed, locally raised cattle are leading farmers and consumers alike to rethink beef. Cattle allowed to forage on fresh pasture can sequester carbon in the soil by promoting new ground cover. Healthy landscapes in turn support more vegetation and wildlife, including birds and beneficial insects. Research shows that grazed areas with healthy soils can support up to ten times more species than conventional pastures. Unfortunately, the majority of American beef comes from feedlots where confined cattle produce vast amounts of manure — turning a once valuable source of fertilizer into toxic waste, polluting soil and ground and surface water and the air of nearby communities.

Unsustainable livestock management practices have contributed to environmental problems by turning grasslands and forests to dust bowls. Over-grazing can compact soils and feedlots can destroy local ecosystems. But there are different ways to raise meat. Many Colorado ranches are raising livestock through rotational grazing and holistic management practices. Lasater Grasslands Beef has thrived using holistic management practices and placing breeds adapted to local ecosystem. Fox Ranch in Eastern Colorado is collaborating with the Nature Conservancy to study the benefits of holistic management practices that help ranchers increase both cattle numbers and grass growth. By frequently shifting condensed herds of cattle to new pasture, Fox Ranch was able to maintain enough grass to build up its herd numbers, even through the two worst drought years.

Slow meat can also help boost local economies by improving incomes and securing a better future for ranchers. Colorado ranchers are faced with a dwindling supply of grazing land and higher land lease rates. By raising slow meat ranchers can maintain healthy grass for their herds while cutting costs on supplemental feed and avoiding additional land leases. Consumers who purchase slow meat directly from producers know that their dollars are benefiting local families. By joining a local meat share, or CSA, and committing to a bulk meat purchase in advance, eaters can contribute towards the costs of raising healthy and humane slow meat. Meat shares can help ranchers secure income and give consumers a better understanding and appreciation of who raises their meat.

This consumer support motivates producers like Bell T Bar Ranch to raise disappearing heritage variety animals. Heritage cattle breeds like the Belted Galloway don’t typically gain as much weight as the common Angus, but they are better suited for cold climates, can forage on rough vegetation, and are deliciously lean.

Attention to animal welfare and environmental responsibility is what attracts most consumers to slow meat, but one of the best perks is the taste. Eaters are realizing that cheap burgers have not only little flavor, but big environmental and social costs. With the success of sustainable meat producers like Lasater in Colorado, White Oak Pastures in the Southeast and Leftcoast Grassfed in California, consumers have demonstrated a demand for better meat giving ranchers even more incentive to produce it. And choosing slow meat is better for both the planet and eaters. Better Meat….Less.

The Five Stages of Field to Fork

Our current practices for maximizing the efficiency of animal agricultural production comes at a cost. We abandon common sense, traditional animal husbandry, land and water stewardship, animal welfare, nutrition, and taste.

Policy experts and food system practitioners, together with Slow Food leaders from all over the USA, gathered to identify practical points of intervention from field to fork. These facilitated discussions addressed how consumers and Slow Food USA communities can begin to turn the herd towards meat that is good, clean, and fair for all.

Here are the outcomes expressed in campaigns for action:

- Campaign for Better Meat: Tastes better, better uses of land and water, better animal welfare, etc.

- Campaign for Less Meat: Meatless Mondays, Meat more as flavor and less as focus of meals, etc.

- Campaign for Better Labels: Purchase from farmers where possible, where not possible learn how to make sense of navigation tools (i.e., labels); and where these labels mean nothing (i.e., not 3rd party certified) then support efforts to remove them (i.e., Killing “Natural”), etc.

- Campaign for Whole Animal Butchery: Working with local chapters, chefs, butchers and breeders, stage workshops on how to use the whole animal; stage events, dinners, and spread the knowledge.

- Campaign for Better Meat in Sports Stadiums: Support efforts to yield farm-to-stadium eating. Get slow meats onto the menus at arenas and stadiums. (It’s already happening, see what the NFL’s St. Louis Rams are doing.)

Stay tuned for more as Slow Food USA is planning a follow up conference in 2015.

A Conference Delegate’s Story That Brought Her To Slow Meat

My involvement with Slow Food Chicago (SFC) reaches back 6 years. I’ve served as a volunteer, board member, and events chair – where I spearheaded our annual fundraiser “The Pig Roast” (now known as “The Farm Roast) – and currently serve as Vice-President. Being chosen as Slow Meat delegate was truly an honor. I’m guessing I was chosen not only for my role with SFC, but also because I was a vegetarian for seventeen years and spent much of my life thinking about animals and their welfare. My first intellectual engagement with conscious meat eating was in 2002, when I read Michael Pollan’s “An Animal’s Place” in The New York Times Magazine, one of the most thoughtful essays on the philosophy of vegetarianism from a carnivore’s perspective. This was the first time I encountered a carnivore that gave vegans and vegetarians their due credit for thinking about where food came from. It was also the first time that I understood that one could want animals to live a good life and still feel comfortable eating them. It took about five years after reading that essay to get me back to eating meat. As conscious carnivores, we have a duty to reach across the aisle and find common ground. Through the work of Slow Food I came to realize that I could become a carnivore and not abandon the principles that had been sacrosanct to me. This is the story that brought me to Slow Meat.

As a nonprofit professional and a Slow Food leader, I am used to being part of a team that brainstorms suggestions to a given problem. At Slow Meat, it was a pleasure to be in the unusual role of a spectator, grateful to be able to listen, observe, and ask relevant questions. Through workshops, conversations in the lunch line, on the bus to the sausage making tour, and at dinner with my Slow Meat companions, I learned about everything from the economics of sustainable animal husbandry to the challenges that processors of good meat face in terms of location and FDA policies. The depth and breadth of knowledge from the people attending was profound. There were people from different regions of the country and different backgrounds: non-profit organizations, ranchers, retailers, labor organizers, butchers, chefs, independent producers, Slow Food leaders, and others. Slow Meat provided people with the opportunity to get down to brass tacks quite quickly, not as much interested in bragging about their work or talking in too idealistic of terms as they were in offering their perspective on issues discussed. At all times, our goal was to work together to create loose consensus on steps that would allow us to achieve change in the food system. As I’ve spoken with some of the regional delegates upon return, including high school senior Evan Gunthorp who helps to run Gunthorp Farms in Indiana and was the youngest delegate to attend, people have expressed enthusiasm for the connections that they made this weekend and hope for the future of good work that will come out of this conference.

Coming out of the conference, we all agreed that compassion towards livestock and sustainable methods of production are critical issues that must be addressed. There was consensus that it is important to figure out ways to make this way of life profitable for its producers. Slow Food is most successful as a catalyst, bringing individuals together around important issues. As an educational nonprofit, it is our duty to address the lack of knowledge that the general public has about meat. We must emphasize the difference between good and factory farmed meat and work towards policy changes that will help processors of good products to flourish. We must also reorient the public towards eating “better meat, less,” among other endeavors. The good news is that we have a pretty amazing pool of intelligent, hardworking, and forward thinking people to work with. Slow Meat is a tangible endeavor that will have real roots here in the U.S. and that will give much needed public visibility to our organization. That we might have achievable results from this initiative resonated the strongest with me besides the fact that I left with a full and grateful stomach.

Many thanks go out to the members of Slow Food Denver for hosting us, to Slow Food USA for their tireless work and for essentially getting out of the way to allow folks the time and space to have conversations, to the important facilitators from the Spark Institute that kept the conversation on track and respectful, and to my fellow delegates for sharing your experiences and enthusiasm. Let’s get to work!

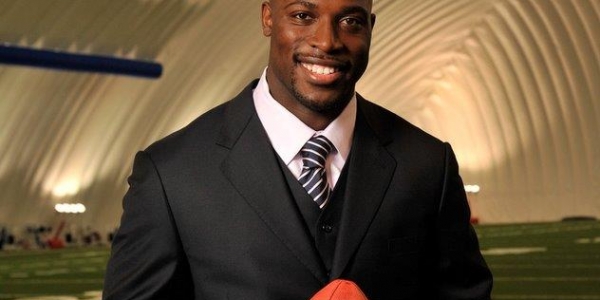

Photo courtesy of Will Witherspoon

St. Louis Rams Stadium Scores a Touchdown with Sustainably Raised Meat

The 2014 NFL season opens with a unique and delicious win for the St. Louis Rams, who kicked off more than a football: Their home turf, the 64,000-seat Edward Jones Dome, is the first to offer sustainably raised, high-animal-welfare hot dogs and burgers to fans.

Even cooler, the better burgers and hot dogs were made possible through the efforts of Will Witherspoon, former Rams’ starting-linebacker last year (and this year’s sideline commentator) and owner of the sustainable Shire Gate Farm in Owensville, Mo., and Delaware North Companies Sportservice, one of the world’s leading sports concessioners. “I am excited the Rams are taking a stand on sustainable food production,” Witherspoon says. “When the bigger players in the food industry raise their game, and start sourcing local, sustainably-produced food in this way, it can lay the foundations for real change–not just at sports venues, but everywhere.”

Will’s products are certified by Animal Welfare Approved, the most stringent certifier of farms in the US. To meet AWA’s exacting criteria, farms must meet high animal welfare and environmental standards, including being raised on pasture, and must not rely on hormones, growth promoters or non-therapeutic antibiotics (meaning that animals receive antibiotics only when they are sick, not to make them grow faster or to mask the symptoms of overcrowded or otherwise problematic conditions).

“At Shire Gate Farm, we’re committed to producing great-value, wholesome food as naturally as possible. AWA and I see eye-to-eye on how cattle should be raised–outdoors on pasture for their entire lives, just as nature intended,” Witherspoon says. “The AWA logo is our way of showing customers that we really are doing the right thing by our animals, and the environment.”

A Big Win for Health

Unfortunately, when most people think about getting food at the game, they aren’t thinking about what’s healthy and good for the environment. Queue a reel of Bill Swerski’s Superfans, the famous Saturday Night Live skit featuring fans like Chris Farley’s character Todd O’Conner who perennially has “anudder heart attack.”

Thankfully, through this pioneering move, the Rams are putting health first by providing fans with meat that is better for fans. It’s a fact that pasture-raised meat and dairy are lower in calories and total fat, have higher levels of vitamins, and a healthier balance of omega-3 and omega-6 fats than conventional options. Witherspoon agrees, “Hot dogs and burgers are practically shorthand for bad food, but my Grassfed Hot Dogs and Grassfed Ground-Beef Burgers are fit for a professional athlete.”

By eating these healthier burgers and dogs, the Bill Swerskis of the Rams’ fans who are worried about health (and heart attacks) can rest a little easier after the glory of the game wears off. “As a professional athlete, Will Witherspoon understands the direct link between the way we raise animals, the nutritional quality of the meat, milk and eggs they produce, and our own health and well-being,” says Andrew Gunther, AWA’s program director. “As a farmer he’s now applying that knowledge first-hand.”

Sportservice Scores a Safety – As in Food Safety

In addition to being healthier for consumption, Sportservice is also living up to its global stewardship platform by serving meat from farms that aren’t reliant on antibiotics, thereby helping to reduce the risk of an outbreak of drug-resistant infections.

While treating sick animals with antibiotics is fine, it’s the undisciplined, freewheeling use of antibiotics that causes problems. Factory farms use antibiotics to spur on growth and to prevent their animals from getting sick in the unsanitary environment in which they’re forced to live. By routinely feeding livestock antibiotics unnecessarily, factory farms become breeding grounds for drug-resistant germs. According to the FDA, 55 percent of ground beef, 69 percent of pork chops and 86 percent of ground turkey were contaminated with drug-resistant bacteria in 2011.

Making the Two Point Conversion…to Sustainability

Seriously, last football pun. Not only is the Rams’ choice to serve AWA-certified meat great for fans’ health, it’s also a great move for the environment. There is a huge difference between farms like Witherspoon’s Shire Gate Farm and the majority of big players in the US meat production industry. For one, factory farming (aka industrial livestock production) is terrible for the environment.

Industrial livestock production generates a huge amount of waste, which pollutes air, water and soil, resulting and degradations to the natural environment. Outcomes of this pollution are all over the news, for instance: Lake Erie’s recent algal bloom. While all meat production draws on resources and all cattle create some waste, AWA-certified farms are dedicated to lessening and mitigating their environmental impact. The AWA certification ensures animals are raised in a manner that results in lower overall emissions of greenhouse gasses and ensures manure is managed sustainably.

So all in all, the Rams’ decision to sell responsibly produced meat is a win-win for lovers of the game and for lovers of the environment. It’s one more example of how sports and sustainability are a winning combination. While the Super Bowl is a long way off, it’s obvious to us the Rams have won another important championship: the Supper Bowl of course! (Okay, that was the last football pun.)