Photo: Aorta

One autumn afternoon in 2015, Danish chef René Redzepi is thinking hard about his restaurant’s place in the world, both philosophically and geographically. “People consider Noma to be a local restaurant,” he says. “We might be culturally local, but ‘local’ in terms of food miles – what does that mean? There are no definitions of these things. According to some 2008 Farm Act in America you have to source within 400 miles, which is like 650 kilometres, which makes us actually a Polish restaurant as well.”

Redzepi, a youthful 38-year-old with a sweep of floppy brown hair, who bears a resemblance to the comedian David Mitchell, is sitting at the corner of a long table up a flight of stairs from his restaurant, Noma, which is located in a former 18th-century warehouse remodelled in 2011. The waterfront neighbourhood in central Copenhagen reflects its maritime heritage: the warehouses once stored salted fish, whale products, oils and skins from the entire north Atlantic region.

The space, known as the Food Lab, was designed by Danish architects 3XN, and contains an office space with modular furniture, a hydroponic herb garden (nasturtium, lemon verbena, St John’s wort, lavender) and seating for staff meals. Redzepi wears chef’s whites and a black apron. When he talks, he layers thought after thought, linking them carefully and building rounded, considered answers.

René Redzepi in the Noma kitchen. Photo: Aorta

He has been a playful presence throughout the day (Redzepi has a talent for mimicking accents – his cockney is more Danny Dyer than Dick Van Dyke), as waves of people have passed through the space. Interns, who listen to death metal and hip hop while breaking down the raw products that arrive at the restaurant, come from the prep kitchen next door to sit and eat (the meals are less expansive than you might imagine – cheese on toast for lunch, poached fish and salads for dinner). Around 3pm, foragers who scour the coastline and woodland sourcing the seasonal products that are intrinsic to Noma’s identity – scurvy grass, samphire, pea shoots, beach mustard, purslane, beach beets, sea arrowgrass – arrive carrying large plastic baskets that have been emptied in storage sheds downstairs. Throughout the afternoon, groups of well-heeled diners are given tours of the Noma facility, snapping photos of the test kitchen, which turns out six new dishes per week (each dish taking 80 to 90 hours to develop). The herb garden fills the room with an earthy, organic smell. There is a large rack of shoes by the door – everyone at Noma puts on Birkenstock clogs when they enter the workspace.

When Noma opened in February 2003, the restaurant’s philosophy was that the food should be based on the geography from which it was being sourced. The notion was complicated and had limitations for an ambitious chef who was interested in creating something entirely new. Redzepi didn’t want to take ingredients and simply adapt them to existing recipes, yet this was what was happening in his kitchen. “I knew that the cooking was good, but it wasn’t our own,” Redzepi says.

Noma was voted the world’s best restaurant by Restaurant magazine in 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2014. During this time, a new sensibility began to emerge. The team began to realise that they had been constricted. To do something original they were going to have to break away from the format of the western tasting menu, which remains largely unchanged throughout the year. As Lars Williams, the chef who heads Noma’s R&D, says: “When Noma opened 12 years ago, it was a laughable idea that you could make a gastronomic restaurant with Nordic ingredients: if you were a high-end restaurant you had to have French pigeons; you had to have foie gras; you had to have caviar. To think that you could make a compelling restaurant with the local ingredients that we have here was a joke.”

Arielle Johnson, head of research for Noma’s food symposium MAD, in the fermentation lab at Noma. Photo: Aorta

Noma struggled to find what it needed during the freezing Nordic winters. Onions would have to be sourced from Stockholm or Hamburg, which are, respectively, 700km and 300km away. However, there were other ingredients that were – and are – plentiful. “This is the time when fish are abundant,” Redzepi says. “The flesh is the most firm that you can imagine, their bellies are full of roe and all the other innards are pristine – the liver, the milk and so on. It’s also the moment when all of the shellfish is at its best – bucketloads of urchins, oysters, weird clams, weird penis-looking shells. And it dawns on you, why don’t you just focus on that? Why aren’t we then – at that period – a fish restaurant? Why don’t we just cook what’s there?”

The chefs started to look at the flow of ingredients through the months and shifted the menu towards seasonality and locavorism, which characterises every aspect of Noma, from its food to tableware. Redzepi believes that this approach is “going to drive all the questions within food going forward”.

The service kitchen has been rearranged to reflect this: a traditional kitchen is structured along the classic French brigade to cuisine system, a hierarchical approach in which specific chefs have responsibility for sauces, fish dishes, grilling, roasting etc. Noma’s kitchen is more fluid, reflecting a different type of work, the preparation of the veg, roots, herbs and fruits that form the basis for the menu. Remodelled in 2013, the work areas, made of simple black monoliths, resist the rigidity of many kitchens. Each chef must know how to make and plate every dish. No one speaks – it’s impossible to be heard over the music anyway. Tasks are accomplished with a brisk, raw energy that verges on mania.

The dining room at Noma. Photo: Aorta

Grilling is done outside on a charcoal-fired Weber Kettle, which Noma prefers over roasting or a sauté pan: “You get a smokiness to the flavour and much more umami,” Williams says. Both proteins and vegetables are cooked on the grill, the latter with smoked butter, to make them umami-rich. The grill is fired up at around seven in the morning and runs until around 11 at night. Noma gets through three of them per month.

Early in the day, dishes are partially assembled. Some of the work is done with medical-grade tweezers and other instruments familiar to those who perform surgery. The plating process at Noma is particularly complex with multiple items – grilled vegetables, slivers of fish, foams, herbs, grated roe, sauces, vinegars, berries, mosses, rocks – layered on top of each other and arranged in displays that are part dinner, part landscape.

Redzepi likes to create surprises that provoke curiosity and wrong-foot visitors. Spoiler alert: what looks like a floral arrangement when diners sit down at the table is actually an appetiser. His dish “the hen and the egg” requires visitors who have prevailed over Noma’s notoriously challenging reservation system (it might actually be easier to win a Nobel Prize) being asked to crack a wild duck egg on to a skillet heated to 280°C and laid on a bed of damp straw.

“The basis of what we’re doing is the quest for flavour and for deliciousness – that’s our mantra, if we have one,” Williams says.

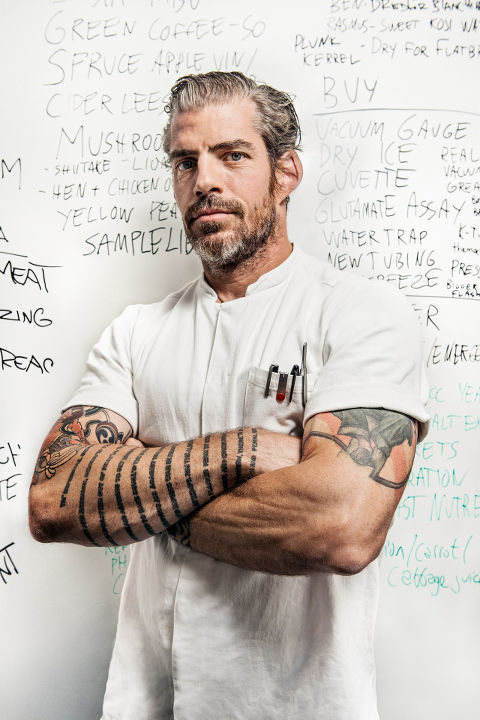

The notion of experimenting with what food could be and how it might be prepared is the job of Williams and his colleague Arielle Johnson. Williams, a New Yorker who perpetually sips black coffee from a tin mug, wears chef’s whites with three pens in the top pocket and black jeans, and has the first 15 lines of John Milton’s Paradise Lost tattooed on his forearm (“Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit/ Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste/ Brought death into the world, and all our woe…”). Before Noma, he and his Danish wife spent a year as private chefs on a boat in the Pacific after meeting at Heston Blumenthal’s Berkshire restaurant The Fat Duck. (Williams also did a stint at chef Wylie Dufresne’s legendary wd~50, New York’s most celebrated destination for molecular gastronomy.)

Arriving at Noma in January 2009, Williams first worked in the kitchen. A year later, Redzepi asked him to take over the Nordic Food Laboratory (NFL) a food-research project that was once a joint venture with the University of Copenhagen. The two have since separated. At that point, NFL was in a houseboat in the harbour next to the restaurant. Its task: to find innovative ways to use Scandinavian ingredients. Williams had been working with wood ants that are found about 25 minutes’ drive from the restaurant, investigating various possibilities for flavour and taste. He had found one species in the woods near Copenhagen that had a powerful ginger-lemongrass flavour and was interested in finding out why the ant tasted that way. After trawling through patents and academic papers he had discovered a document that illustrated the chemical structures of different ant pheromones and how they relate to flavour. But then he had hit a dead end. He was puzzling over the diagram on his desktop when Johnson, who was working at the lab for the summer while completing a PhD, came by and examined the screen.

“What are you looking at lemongrass for?” she asked.

It turned out that ant pheromones are made of the same molecules that are found in lavender and pine as well as lemongrass.

“Most social insects have some sort of pheromones, but ants seem to have the widest range of flavours,” Williams says. “The ants that we use most in the restaurant at the moment create a sort of acid that’s very lemon-flavoured as a defence mechanism. But they have the capability of producing a very wide range of flavours – orange, coriander or mint.”

Working at the Food Lab is best suited to those who are omnivorous. Williams and Johnson have just come back from a trip to Zimbabwe during which Johnson developed gastric problems – she’s not sure whether it was caused by well water or goat intestines. Despite tasting whatever was at hand, Williams remained in rude health. “It’s my job to eat a wide range of microbiomes,” he says, “so I have a rather robust digestive system.” Later, he recalls a foraging trip in the woods in Japan. “What’s this?” he asked Johnson, holding up a berry he had just tasted. Johnson identified it immediately as the fruit from black nightshade, a highly toxic plant. Williams suffered no ill effects.

One morning in May 2015, Johnson and Williams are demonstrating Noma’s zero-waste composting machine, made by Australian company Closed Loop, which breaks down 100kg of food waste into 10kg of compost in just 24 hours. Williams admits that he’s tasted the compost.

Williams: “The composter works using lactic bacteria.”

Johnson: “Yes, it’s like a thermophilic lactic bacteria, which is the same genre of bacteria as in sauerkraut. It’s very salt-tolerant and very heat-tolerant and very difficult to kill.”

Williams: “And it digests anything you put into compost within 24 hours. I was actually a little bit nervous about eating that.”

Johnson [after Williams ate the compost]: “We were looking up all these papers about it to try to figure out what the thermal death curve of it was.”

Williams: “Also, once I ate it, would I eat it – or would it eat me?”

Lars Williams in front of the planning whiteboard in Noma’s R&D lab. Photo: Aorta

Much of the energy in the Food Lab is put into fermentation. Scandinavia has a strong history of foodstuffs being altered for preservation by yeast and bacteria. The time period for the warmer months is extremely short and there’s a period of high botanic growth, “this burst of vegetation and flavours that you really need to find some way to preserve to make sure you have something to eat,” Williams says.

The Food Lab was conscious that preserved fish and meat were often heavily smoked or salted and the pickling was overly acidic. The team decided to start playing around with fermentation, but focused on flavour, as opposed to how long a product could sit around on kitchen shelves. Asia, specifically Japan, is a significant influence. “With basically rice and soya beans and a thousand years of cleverness, they have fermentation techniques that have created a whole base of cuisine which is incredibly complicated yet elegant,” Williams says.

It seems that the future of food is fungus, specifically the mould Aspergillus oryzae, which is known as “koji” in Japan and forms the basis for much of the nation’s cuisine. (When Williams was visiting once he spent time with tenth-generation koji fermenters and people with “sheds full of squid guts”.) Johnson, 28, was at the University of California, Davis, writing a PhD on flavour chemistry and gastronomy in 2011 when she heard about the work going on in the Food Lab. She remembers thinking: “A restaurant with a lab that’s doing research into cuisine – that’s exactly what I want to do.” In June 2012, she went to work with Michael Bom Frøst – who also held a position at the food-science department at the University of Copenhagen – at the Nordic Food Lab. On her first day, she met Williams and Mark Emil Tholstrup Hermansen, who curates Noma’s annual food symposium, MAD (“mad” is Danish for “food” – it’s the basis of the second half of Noma’s name, a contraction of “Nordic” being the first). After returning in 2013, Johnson talked her way into a full-time job and moved to Copenhagen as the head of research for MAD. “I’m not sure anyone quite knows what my actual job description is,” she laughs.

The centrifuge in Noma’s R&D laboratory.

Soon after she arrived, the restaurant took delivery of four shipping containers. Two of these have become the latest repositories of Noma’s quest for the new or, as Williams has it, “the Domesday project”. The “office” for the R&D lab is a container perched on top of another with a couple of windows cut into them, an old IKEA kitchen, a second-hand bench, and various culinary and scientific devices such as a centrifuge (“it’s great for things like clarifying juices, nut milks and rose oil,” Johnson says). It’s reached by a steep metal staircase that’s as close to being a ladder as steps can be.

The containers have been divided into seven chambers that vary in temperature from -30°C to 60°C and zero to 100 per cent humidity. With close to zero budget, Williams and Johnson jerry-built a solution. “I spent a week wiring the thing,” Williams says. “We finally got online on a Tuesday at two in the morning.” Johnson needed to reprogram all the controllers.

The hottest chamber is what they refer to as the garum room (garum is a fermented sauce made from the blood and intestines of fish, beloved by the Romans). Here, most of the contents are protein ferments that are enzymatic, which means that they have a sweet spot of around 55°C to 60°C. “They’re very, very active,” Williams says. Vegetable-based enzymatic ferments such as black garlic are developed in an adjacent compartment. There are other rooms for growing Aspergillus oryzae which is calibrated to 33°C-35°C in strong humidity. The chambers are together because of thermal bleed.

In September, a time when there’s a high degree of harvesting, one of the rooms is set up as a giant dehydrator that’s maintained at around 40°C; air with zero humidity is pumped through to aid the drying process. There’s a vinegar room and another for lacto ferments where the kombuchas (fermented green-tea-based drinks) are developed. Both are in sealed containers and require a similar temperature range, so can be stored together. When duck season opens in the autumn, game curing begins. (Storage is a big issue at Noma: Williams and Johnson recently made 100kg of soy sauce from discarded cabbage leaves, but hadn’t thought about where they might store it.)

In conversation, the pair move quickly through different food groups. Johnson talks about how they are “playing around with mackerel” and Williams adds that they “had a lot of grasshoppers around at the time”. They tried to make garum from grasshoppers and discovered that it “contains a good amount of protein”. The garum conversation continues. It’s agreed that razor clam garum has similarities to soy sauce and that squid garum is the closest there is to the Roman iteration.

“There are a lot of things that are happening in food now, especially in restaurants, that science can be applied to; it’s just that the work hasn’t been done yet,” Johnson says. “If you start bringing a bit of knowledge about the biochemistry of micro-organisms or the chemistry of flavour compounds and substrates, you can get a lot more precise in how you’re fine-tuning things.” Williams describes their methodology as “natural biotech”: fermentation is a kitchen tool in the way that a frying pan or an oven might be used.

“You sometimes hear about scientists working with food and it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re bringing rationality into the creative process,'” Johnson says. “No, I don’t want to bring rationality to the creative process at all, because that would ruin it. Science is not here to tell you what tastes good. Science is here so that you know how stuff works and that in turn lets you be creative with what you have.”

[WIRED’s Inside Noma video]

By the end of 2016 Noma, in its current form, will no longer exist. In January the entire restaurant – all 80 members of staff – decamped to a warehouse in Sydney to reimagine Noma in Australia. As with a residency in Tokyo in 2015 (and, to a lesser extent, a pop-up in London hotel Claridge’s in 2012), it involved not only creating entirely new menus from native produce, but moving 80 staff and their families to a new city thousands of kilometres away for a five-month period. Noma is due to reopen in Copenhagen in May 2016 but will then close at its current location – for good – at the end of December.

Redzepi and his team have found a new, bucolic site on which to launch a much larger and even more ambitious project. A five-minute bike ride north-east of Noma – skirting the hippy-anarchist commune Christiania – is an ex-military warehouse which once stored mines for the Danish Navy.

Ash-coloured clouds skim across the sky as head of development Mark Emil Tholstrup Hermansen strides up pre-war brick steps that lead on to the roof of the building on a strip of reclaimed land between two lakes. Hermansen, an Oxford-educated, Morris Minor-driving social anthropologist, has guided the MAD symposium to becoming perhaps the most influential gathering of forward-thinkers about food. He has been part of the team that, for the past three years, has secretly worked on the project to move Noma to an entirely new site that will be designed by the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels. “We’ve been learning and researching how to cook for this region for the past few years,” Hermansen says. “Coming here allows us to make the restaurant we’ve been practising for.”

Currently the site is abandoned and has been taken over by graffiti artists – what must be thousands of empty cans of spray paint litter the floor. The one-storey property is 100 metres long – far bigger than the footprint of the current restaurant. It will have space for offices and a gym as well as more ambitious elements of the trade, such as a smokehouse and stone ovens. But the setting – on a lakeside, surrounded by trees and nature, with a modern housing project on the other side – allows the team the opportunity to create a garden for herbs and vegetables and floating platforms on the lake for growing produce. A greenhouse will be constructed on the roof to grow ingredients that are unavailable during the winter. Much of the greenery on the disused property consists of wild berry bushes, which will be left as they are. “We won’t make it too manicured,” Hermansen says.

Mark Emil Tholstrup Hermansen, head of development, has been working to move Noma. Photo: Aorta

“What we want to do is to change the world through food,” says Mark Emil Tholstrup Hermansen, the head of development at MAD, Noma’s not-for-profit that works to expand knowledge about food. The annual MAD symposium, which started in 2011, has hosted not just presentations by some of the world’s most famous chefs but talks by chemists, farmers, entomologists, agronomists, activists and an urchin diver. Beyond this, MAD produces compendiums of writing about food, has launched a digital platform on wild food and foraging for both schools and adults, has devised a management programme for Yale and consulted for the World Bank. “The creative potential of the chef is only expressed through restaurants, but food is at the intersection of politics, nutrition, geopolitics, culture, jobs, hunger and deliciousness.”

The new Noma will continue its relationships with its current producers and suppliers, but the site will offer some fresh opportunities: the restaurant will produce more compost, which will be shared with farmers, and Noma chefs will learn to work the land and to further understand the relationship between it and what ends up on the plate.

“During the winter, we can grow what we need and try to be self-sufficient,” Williams says, standing before the lake that future Noma diners will gaze upon from their tables. “Everything that comes on to the plate will have been made ourselves. This allows us to control every aspect of what we’re doing.”

Inside the warehouse a graffiti artist is working on a green outline to a large letter G. Stepping over discarded bottles and remains of campfires, Hermansen, Williams and Johnson sketch out the layout – a fermentation kitchen, test kitchen, a workshop for the fabrication of plates and cutlery, front office, an office for the MAD group, a gym, a staff meal area, the prep kitchen, service kitchen and – the tip of the iceberg – the dining area, which will be similar to that used today.

“We’ve taken steps to understand what the next decade of work is,” Redzepi says. “Everything we do should have long-term thinking.” He is aware that Noma is a restaurant with just 12 tables, but that doesn’t dull his ambition for its influence. In autumn 2015, MAD launched the National Foraging School, a programme for both adults and schools (“it will enrich [the children’s] lives and it will hopefully connect them to nature in a more profound way,” Redzepi says), and a Noma executive leadership programme will take place at Yale for the first time this spring. Redzepi admits that it has taken years for him to calibrate his own leadership style. “I had to physically remove myself from some situations,” he says. “It was a very big decision.” What he means is that he no longer oversees service as he found it difficult when things weren’t done exactly the way he wanted them to be.

René Redzepi prepares the chocolate-covered lichen. Photo: Aorta

Spend time at Noma and what becomes clear – through the restaurant, the R&D lab, the MAD symposium and the relationships that the restaurant has built with its suppliers and broader network – is that Redzepi wants to build something more expansive than a restaurant: a global community through food.

“If you can encourage a spirit of saying that, if we can work together as a growing community, we’re all part of the same organism,” he says. “We’re all doing our different thing but we are part of the same organism which is exploring life through food and putting all these things in the equation, like team work, sustainability, financial success. If we do it together we will be individually more successful in the end.”

This enables the Noma team to develop an entirely new menu based on geography – wherever they are. The process begins with the team tasting as many products as possible and then creating a series of condiments based around the products that reflect the area. Only then does the process of building dishes start. Williams talks about recent trips to Japan and Zimbabwe: “You use your intuition to let the natural taste of products guide you to how you can slowly twist and shape them into something else.” In Sydney, the kitchen and dining room are being built from scratch. The schedule will be intense: Williams spent Christmas Day 2014 plucking one hundred wild ducks in preparation for the opening of the Noma pop-up in Tokyo.

Don’t miss Noma’s food as you’ve never seen it before…

The new urban-farm iteration of Noma will further develop a community around the restaurant and perhaps have a broader impact on how human beings eat beyond the higher echelons of gastronomy. Noma’s suppliers must all pass a rigorous quality-control process. Williams jokingly describes the butter supplier as “an extremist”. “All he cares about is making – and innovating – in butter,” Williams says. Experiments have included “bog butter”, which was inspired by 18th century Scots who buried the product in peat, and filtering the milk through hay so that its particular bacteria would infuse the milk with flavour.

When Noma opened it was set among derelict warehouses. Now it is surrounded by recently constructed waterfront condos. A pedestrian bridge connecting the restaurant to the central part of the city is nearly complete. Workers in hard hats and hi-vis jackets scurry on top of the concrete arc. Just one 20-metre expanse remains before it’s complete and Noma is no longer an outpost. It’s time to move on.

“You’re spending most of your income as a restaurant on experimenting – that’s very expensive,” Redzepi says. “So you have to recognise that you do it because you love learning new things and exploring the world, meeting new people. And then you have to understand that you’re asking people to go to work and feel miserable most of the time because that’s what failure does to you. It’s really tough. How do you create an environment that has a spirit in which that’s OK? At Noma, decisions come from the gut, and what we feel is necessary. Having a good balance between work and family and expanding the community, taking lots of risks – you have to be willing to risk everything.

“You have to say, ‘We take a risk now that might mean Noma is not here in two years.’ Can I live with that? Yes, I can.”