ON A FOGGY , cold, damp afternoon last week, I find myself atop Garvin Mesa, three miles north of downtown Paonia. Here at 6,210 feet above sea level, a steady drizzle and bone-chilling wind whips Desert Weyr Farm. Its residents, however, couldn’t seem happier.

“Look at them out here — they’re just hanging out in the rain,” says owner Eugenia “Oogie” McGuire, leading me on a farm tour despite the inclement weather. “This is the shelter for the rams all winter. [They’ll be] lying down with nine inches of snow on their backs, sitting there, chewing their cuds, just perfectly fine. They’re very tough sheep.”

Photo credit: Aspen Times

Such harsh conditions are similar to those in Wales, where these native Black Welsh Mountain sheep have been bred for thousands of years on rocky terrain. The rams in this pasture — and ewes and lambs separated by yards of fencing, to prevent breeding outside of specific periods — are jet-black, with thick, coarse wool and delicate bones. They look like horned bricks of charcoal teetering on spindly legs. When McGuire calls out to them — “Ba ba ba, ch ch ch ch ch ch ch ch” — they respond with a few bleats before returning to chomping wet hay.

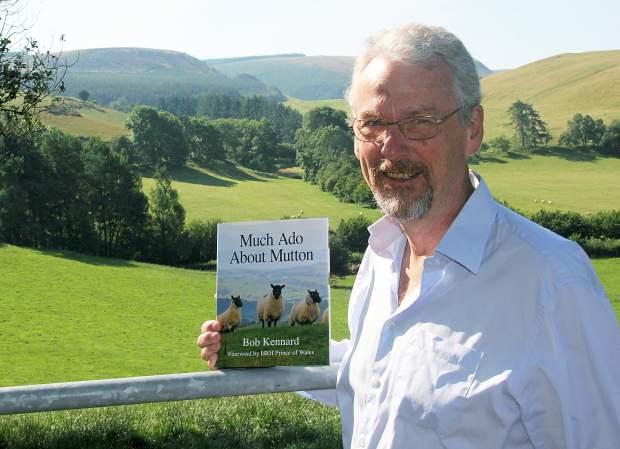

“They’re extraordinarily calm,” agrees Bob Kennard, AGE, a former shepherd and expert in artisanal mutton production, visiting Desert Weyr from his native Wales. “Our farm is at 1,100 feet — in the UK that’s quite high,” Kennard says. “We get a lot of snow and a lot of bad weather from the Atlantic. The Victorians said that the upland breeds such as these were the best because they had no external fat and good marbling of the meat, which adds to the flavor. We have one of the best breeds in the UK producing mutton here, which is fantastic.”

Photo credit: Aspen Times

By maintaining a flock of about 60 Black Welsh Mountain sheep and selling their wool, manure, horns, and meat, the 40-acre Desert Weyr Farm is leading the conservation effort of the breed, which is considered rare and endangered in North America. As one of the foremost experts on the species and author of the recently published book, “Much Ado About Mutton,” Kennard has made a maiden voyage to the States to help expand the UK’s “Mutton Renaissance” overseas.

“Our rams have particularly nice temperaments,” McGuire continues, “because we’ve eaten all the bad ones.”

Photo credit: Aspen Times

That’s the irony of McGuire’s work to protect Black Mountain Welsh sheep at Desert Weyr for the past 15 years: “We can’t guarantee genetic diversity unless those animals have a job,” she says. “We need consumers to support rare breeds, and the best way to support a rare breed is to eat it.”

Mutton meat is making a comeback in North America, and Desert Weyr is leading the charge. Black Welsh Mountain sheep were first imported from the UK to Maryland in 1973; the founding genetic population consisted of just two rams and nine ewes. In the late-1990s, Desert Weyr, then run by McGuire’s mother, was one in a group of breeders responsible for growing the flock. Today, McGuire maintains a flock of about 60 breeding ewes and three of the eight original bloodlines. There are only about 1,600 Black Welsh Mountain Sheep in North America, and fewer than 10,000 worldwide. Three years ago the McGuires created LambTracker, an open-source software system for shepherds to use to streamline operations.

Photo credit: Aspen Times

Following Kennard’s Rocky Mountain sojourn, which concludes with a book signing at the farm on October 31 during the annual end-of-season Celebrate! event with locals wineries …, the Welshman continues to California to speak at the American Livestock Conservancy’s annual conference on rare breeds.

“This year the focus of the meeting is on flavor,” McGuire quips. “Mutton is flavorful!”

Photo credit: Aspen Times

Unfortunately, the word ‘mutton’ is often enough to turn off the most adventurous foodies. “There is a psychological barrier to us eating mutton,” declares Kennard, who was in the meat business for more than 25 years in the UK beginning in the late-1980s. In 1990 he turned to organic mutton production, following a decades-long decline. “I couldn’t understand why it was so popular in Victorian times — there was more mutton meat than beef in the UK during the Victorian period. Why did it disappear?”

Of many reasons, World War II tops the list. GIs in Europe and elsewhere were fed with canned mutton — mostly from Australian merino sheep, which have fine wool but sub-prime meat. “Because of food shortages, we ate anything,” Kennard explains. “The quality of our meat sunk. It got into the folklore: Mutton is always going to be tough.”

The Industrial Revolution also swung preferences toward lamb, as the burgeoning population meant more mouths to feed and mutton production simply took too long. (In the UK, mutton are sheep two years of age or older; in fact, Victorian Era eaters preferred mutton at 4 or 5 years old.) For the first time in 6,000 years, sheep were used primarily for meat as opposed to wool, milk, and tallow.

Photo credit: Aspen Times

In 2004, the Prince of Wales started a campaign “to try and build back the idea that mutton is a food icon that should be enjoyed,” says Kennard, who works with the UK National Sheep Association and uplands farmers struggling with livestock prices. “We want to create a quality market for older sheep, to bring back this fantastic meat.”

Together, Kennard and McGuire are out to slay misconceptions about mutton, whose flavor is affected by breed, forage, and aging. Black Welsh Mountain sheep — entirely grass-finished at Desert Weyr—are a choice species.

“People think it’s going to be really strong or gamy, but it’s not,” Kennard says. “It’s a completely different meat, like veal to beef.”

Coloradans are onboard. Desert Weyr Farm sells mutton meat — including ribs, ground meat, shanks — and products including a new sweet Italian mutton sausage on the farm by appointment in the winter, at Lizzy’s Market in Paonia, and to select restaurants in Aspen through the new Farm Runners delivery service. Most popular is a smoked kolbasi mutton sausage, served as “baa-twurst” at Revolution Brewing in town.

“A lot of people are like, ‘Oh, mutton, I don’t want that but I really need to eat something,” McGuire says of brewery patrons faced with the limited snack option. “It is hard to get people to try it, but once they do, they like it.”

I witnessed this mutton hesitation firsthand at Taste of the Valley in Carbondale back in September. Megan MacMillan, chef-proprietor of Paonia’s North Fork Foods in Paonia, prepared a dish of mutton kofta meatballs on the demonstration stage. When samples were ready, the audience hesitated. However, approving murmurs soon followed those tentative first bites dipped in Greek tzatziki. Prime mutton meat is rich and flavorful—sort of a cross between beef and lamb with a touch of ranch-raised elk.

“We’re selling the experience of the flavors and the story of the animals,” says McGuire, who is experimenting with smoked mutton ham and mutton bacon. She backs all products with a 100 percent satisfaction-or-money-back guarantee. “Some sheep,” she says, “belong on a plate.”

MAKE IT:

Photo credit: Graig Farm Organics- Tagine of Mutton with Chick Peas

Tagine of Mutton and Chickpeas

“Mutton is one of the prime meats, and it is one of the most expensive meats,” says Eugenia “Oogie” McGuire of Desert Weyr Farm in Paonia. “Veal is a baby cow or steer, and a well-aged steak is an older animal. They’re both good, but slightly different. That’s the difference between lamb and good mutton.” This recipe, excerpted from “Much Ado About Mutton” by UK expert Bob Kennard, uses a fail-safe method to prepare the flavorful meat rich in vitamins, minerals, and omega fatty acids: slow cooking.

Serves 6-8

2 1/4 pounds diced mutton

4 Tbsp. olive oil

2 onions, finely chopped

6 garlic cloves, crushed

1 tsp. ground coriander

1 tsp. ground cumin

1 tsp. ground paprika

1/2 tsp. ground ginger

1/2 tsp. ground cinnamon

1/4 tsp. chili powder

1 Tbsp. all-purpose flour

28 oz. canned, diced tomatoes

1 cup water

14 oz. chickpeas, drained

1/3 cup raisins

Salt and pepper

Mint or coriander, to garnish

Heat oven to 325°F.

In a large, heavy casserole set over medium flame, heat oil. Add onions and cook until softened, about 5 minutes. Add garlic and spices and cook, stirring, until fragrant, about a minute. Add mutton, sprinkle in flour, and stir until coated with spiced mixture. Cook gently until lightly browned, 10-15 minutes. Add tomatoes and water, mix well, and bring to a simmer.

Cover casserole dish, transfer to preheated oven, and bake about 1¾ hours.

Remove dish from oven. Stir in chickpeas and raisins and cook another 30 minutes or until meat is tender. Add salt and pepper to taste.

Serve hot, garnished with herbs, over buttered couscous or mashed potatoes.