Ever heard of Purple Ribbon Sugarcane or the Carolina African peanut? We hadn’t either. And how could we? There are loads of delicious staple produce and grain that were once essential to eating in the South that are now extinct—or severely endangered. That’s why professor David S. Shields is trying to revive the best-tasting produce and grains from Southern history and bring them back to life (and our dinner tables). We spoke to Shields to learn more about his new book Southern Provisions, food in the Lowcountry, and how exactly he’s resurrecting extinct ingredients.

Bradford Watermelons today. Photo: Facebook/Watermelons for Water

Tell me a little bit about the work you did for Southern Provisions.

Take the Bradford watermelon as an example. The melon was one of the greatest-tasting melons of the antebellum period and it was rediscovered three years ago.

What happened to it?

When Civil War ended, the South was left in economic disarray. Instead of going back to the old plantation system and cotton, it went into truck farming, providing fruits and veggies for the northern markets. These watermelons created a sensation in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. The farmers in the South couldn’t grow them fast enough. The Bradford watermelon has this rind that is rather tender, so they didn’t ship well. They would crush if you stacked them more than two deep. So, the farmers figured they had to breed this melon with another melon. The new melon didn’t taste as good; flavor, which was the premium for the Bradford, was supplanted by shippability. By the 1890s, the abundance of watermelon fields became vulnerable to disease. And, all of a sudden, a disease-resistant watermelon became first priority. Then shippability at number two, then taste. For me, Glenn Roberts [founder of Anson Mills], and other people in our network of restoring ingredients, it’s taste.

Author David S. Shields and his new book Southern Provisions. Photo: University of Chicago Press

Some of the grains you research are extinct. Can they be revived?

There are a couple of ways that we can do things. We can de-extinct things genetically. For example, there are all of these offspring [sugar]canes that were bred from the original. So, you get a genetic fingerprint and then back-breed what’s available into the old cane.

What about the non-genetic way?

Most things are preserved somewhere. Maybe it’s been mislabeled and people don’t realize what they’ve got. One of our most recent discoveries was wheat called Purple Straw. It was mid-19th century wheat that was bred in the 1840s and 1850s for resistance to pests afflicting the fields back then. While researching, I noticed that Purple Straw Wheat was not from the 19th century. It was actually ancient wheat that survived. And I realized that it’s the original Southern whiskey wheat. It’s also the very first biscuit wheat.

The very first biscuits ever made used Purple Straw, an ancient wheat, said Shields. Photo: Jesse David Green

If things are extinct, how do you know what’s worth reviving?

There’s no Wayback Machine that’ll take you back. But you do have testimonials. For example, there are these hyper-aromatic strawberries we’re working on. Preserve makers used to describe opening a jar lid and a cloud of perfume that caused every head in the room to snap in your direction.

Will these ingredients ever be widely available?

Some of these old plants have to use pre-industrial agriculture farming methods. It’s definitely more expensive.

Chestnut varietals are among the ingredients Shields and others are reviving. Photo: Christina Holmes

Any ingredients in the works at the moment?

Chestnuts. There was a whole set of chestnut foodways not just in the South but also in the Northeast, Midwest, anywhere they grew. There were chestnut grits, chesnut-fed hogs and venison, and chestnut skillet breads. So, we’ve done the research—getting the recipes, etc. So far we’ve made chestnut skillet bread and barbecued a chestnut-fed hog. We worked with a chinquapin, a dwarfed cousin of the chestnut, too. We handed some over to Travis Milton [chef at Comfort in Richmond, who recently left to open his own restaurant] and he made a salt-rising bread and mortadella using venison instead of pork and chinquapins instead of pistachios. But it’s very difficult to get the burr off of the nut—it cost us $125 a pound to do it. If that’s going to be viable, we’ll have to figure out a way for that to work.

Have other chefs taken to this project?

This is the way the culinary world works. If you bring back a taste that is splendid and people taste it, they’ll find a way to use it. But it’s important to note that we’re not into re-enactor cuisine. What we’re interested in is the greatest: the best corn, the best rice. Big Jones in Chicago works with us; in Charleston, Husk. Then there’s The Shack Restaurant in Staunton Virginia, Comfort in Richmond, some of Ashley Christensen’s restaurants in North Carolina.

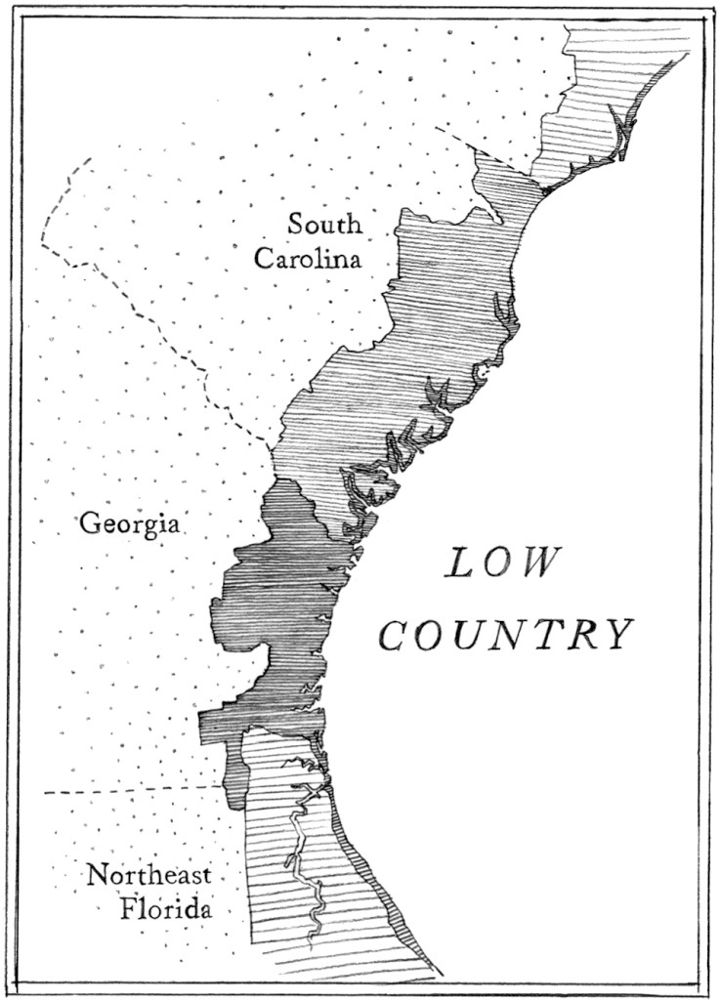

An illustration from Southern Provisions depicting the Lowcountry. Photo: University of Chicago Press

How would you define Southern cuisine?

Southern cuisine is a cuisine that has corn or rice as its central grain instead of wheat and barley. The hog is its principle meat, rather than beef. It combines European, African, and Native American ingredients and attitudes to create a distinctive, local taste that has both a refined city cuisine and a down-home country style.

If you look at what was sold in the Charleston in the 19th and 20th centuries, a lot of it came from Cuba, and Cuba was importing a lot of Carolina gold rice. So, I view Southern cuisine as an expansive thing with global dimensions: Why are all of these seafood recipes from the south made with Worcestershire sauce? What was the fascination with curry? It happens if you go to a Southern Garden, too. You see Chinese crape myrtle trees and gardenias from South Africa. Now, nobody thinks twice about it—they’re Southern.